©UNHCR/Daniel Dreifuss

Protection risks during Covid-19 Pandemic

The qualitative and quantitative data for this study was collected prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in the region. Public health measures adopted by governments in the framework of the pandemic have had an important impact on the dynamics of human mobility worldwide. Strict limitations on movement and border closures have affected the overall options for protection of people at risk, particularly in the countries in northern Central America: El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. At the same time, the many forms of violence and persecution that have driven forced displacement in this region for years on end, have continued and, in some instances, worsened during confinement.

In the context of the pandemic, community leaders in areas where UNHCR works in northern Central America report an increased vulnerability to persecution. The persons targeted by the gangs are more easily located by the gangs due to the confinement. Leaders have also reported that community members have faced difficulties in accessing food and medicine during this time as a result of the control exerted by these criminal groups. In addition, workers in the transport sector, a frequent target of extortion by gangs across the subregion, have expressed fear that once confinement eases, extortion actions by criminal groups will resume.

Additionally, UNICEF offices in these countries identify an increase in reports of domestic violence since the beginning of the pandemic, while child protection services have been cut back. Similarly, sexual and gender-based violence, particularly within the domestic context, is also on the rise. Confinement measures established in several countries increases exposure for women and girls to their aggressors and in turn limit their opportunities to seek help or flee from perpetrators. In Guatemala, 25,400 crimes against children were reported between January to November to the Public Ministry ; in El Salvador, civil society organizations reported a 70 percent increase in domestic violence in April and May; and in Honduras, more than 40,000 reports of domestic and intrafamily violence were reported between March and May through the 911 reporting line, reaching the highest number of complaints in the month of April with 10,000 reports. Data from a rapid household survey conducted by UNICEF in Honduras (2020) show that practically half of the households interviewed perceive that internal conflict at home has increased during the quarantine. In another survey undertaken by UNICEF in Honduras among a group of young people and adolescents, 27.1% of those consulted perceive that those most affected by tensions within the home are children.

In a survey undertaken in Guatemala in June by CID/GALLUP in partnership with UN agencies on the impact of COVID-19 on the population, half of those surveyed indicated that they had stopped buying food due to a lack of money and 50% perceive and increase in intrafamily violence. 15% said they had heard of or knew someone who would be leaving the country due to the economic crisis and increase of violence in the context of COVID-19. Between March and October, more than 3,330 unaccompanied children (2,354) and accompanied children (992) were returned to Guatemala from Mexico and the US. This reveals that children and families have continued to leave their country during the pandemic.

Violence also affects other specific population profiles, including members of the LGBTI community, whose leaders have reported hate crimes and discrimination amidst the pandemic. It is expected that as movement restrictions ease, more people will flee –internally or across international borders– to escape extortion and violence by criminal groups, domestic violence, as well as other human rights abuses, amongst other push factors.

As a result of border restrictions in Central America and despite Mexican authorities’ decision to treat the reception of asylum claims as an essential activity, the average number of asylum claims registered plummeted from a monthly average of 6,000 in January and February, to only 1000 claims in April in Mexico. However, in the context of COVID-19 there are still thousands of people internally displaced in their own countries or fleeing irregularly to apply for refugee status in Mexico. These numbers are expected to increase exponentially following the lifting of COVID-19 restrictions, as partially shown by the 3400 registered asylum claims in September, despite partial mobility restrictions still being in place.

Changes in immigration, border enforcement and asylum policy in the United States of America (U.S.) have also had an impact on the regional protection space and returns to Central America. Asylum seekers’ access to U.S. territory were impacted in some border sectors by the introduction of “metering” (limiting the number of individuals who are permitted to access the asylum process each day at ports of entry) as early as 2016, but was expanded border wide in 2018. In January 2019, the U.S. began to implement the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), through which asylum seekers from certain countries (Spanish-speaking countries plus Brazil) could be returned to Mexico while waiting for the resolution of their U.S. immigration proceedings, including asylum claims. In September 2019, another regulation prohibited the consideration of asylum claims of people who had transited through a third country prior to reaching the U.S. southern border. In November 2019, bilateral agreements dubbed “Asylum Cooperation Agreements” (ACAs) were signed between the United States and Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, respectively. These allow U.S. officials to remove certain asylum seekers arriving at the U.S./Mexico border to the ACAs signatory countries to seek asylum there, rather than allowing them to apply for asylum in the United States.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic complicated the landscape even further, with the March 2020 adoption of an order from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), based on Title 42 of the U.S. Code. This order restricted access to U.S. territory for all unauthorized individuals, including asylum seekers, at the northern and southern borders. More than 328,000 people were expelled from the U.S. to northern Central America and Mexico between March and November 2020, including at least 13,000 unaccompanied children. These add to the ongoing deportations of asylum seekers and migrants –referred to as “assisted returns” under Mexican law–, including unaccompanied boys, girls and adolescents. Many children of all ages have been sent back with no screenings for international protection needs or family reunification claims, as well as without best interest procedures, vulnerability assessments or family tracing. In such cases, there is rarely preparation for return or reintegration assistance, heightening the protection and health risks for children during their return from Mexico and the United States to Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.

Shifting Demographics

Focusing on the demographics of human mobility along the corridor from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras towards Mexico and the U.S., there has been a notable increase in the number of families over the last few years, either in small groups or as part of large mixed movements, commonly known as caravans.

According to figures from U.S. Customs and Border Protection, between October 2018 and July 2019, total apprehensions increased by 139 percent at the southern U.S. border. Although the number of unaccompanied children apprehend increased by 68 percent, the most alarming figure was that of apprehended families which, soared from nearly 77,800 families in 2018 to more than 432,000 in 2019, representing a 456 percent increase.

Apprehensions at the southern U.S. border

Apprehensions

2018

2019

% increase

Unaccompanied children

Family units

Single adults

Total

Table 1. Apprehension of people by Border Patrol at the U.S. southern borders, fiscal year comparison 2018-2019 (from October 2018 to July 2019). Source: CBP: (2019c).

These figures constitute a demographic shift in comparison with the trends registered between 2013 and 2018, when the large surge from northern Central America towards Mexico and the U.S. was disproportionately unaccompanied children. According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection, while a total of 10,443 unaccompanied and separated children from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras were apprehended during fiscal year 2012, this number had doubled to 21,537 during fiscal year 2017.

Meanwhile, since 2018, Mexico has also registered an increase in the percentage of children from northern Central America fleeing with adult family members as compared to those fleeing alone. In previous years, half of the children from northern Central America registered by the Mexican National Migration Institute (NMI) were unaccompanied, compared with only 32 and 25 percent in 2018 and 2019 respectively, indicating an increase of families as part of this movement of persons.

The number of those seeking international protection in Mexico has increased exponentially: 70,431 sought asylum in 2019, nearly twenty times more than in 2015 when 3,424 claims were registered.

Yearly statistics on families applying for asylum are unavailable. However, UNHCR estimates that in 2019 the average number of persons on each asylum claim from northern Central America was 1.9. Likewise, the asylum claims with children averaged almost 3.3 family members, indicating that most children now flee with multiple family members.

While the focus of this study is on families, it is also worth highlighting that the number of unaccompanied children from northern Central America that have accessed the asylum procedure is limited, despite many of them claiming to have fled violence and requiring protection from return. More than 66,000 unaccompanied children from northern Central America have been registered by Mexico’s INM during the last five years, but only 2,000 of them sought asylum since 2015, below 3 percent.

In November 2020, Mexico published a reform of their refugee and migration laws that represents major progress towards the full protection of migrant, asylum-seeking and refugee children in the country. The changes ensure the prohibition of child detention (including families with children), places the best interest of the child at the center of every decision involving them, and includes access to a temporary immigration status on humanitarian grounds for every child.

Given these shifting dynamics in human mobility in these countries, UNHCR and UNICEF, through the Interdisciplinary Development Consultants, S.A. CID Gallup, decided to undertake this study with the aim of understanding and giving visibility to the forced displacement of families that flee northern Central America. In addition, the study also seeks to shed light on the current trends, protection risks and factors associated to the forced displacement and migration of unaccompanied and separated children.

For this purpose, Gallup conducted 3,104 surveys, complemented by focus group sessions segmented according to the geography of displacement in the region: country of origin, of transit and of asylum. Additionally, interviews were undertaken with families who were part of large mixed movement “caravans” that left Honduras at the beginning of 2020.

The ever-present risk of displacement in countries of origin

There are multiple root causes of displacement in northern Central America that are all too often linked together with violence. By the end of 2019, nearly 800,000 people from El Salvador Guatemala and Honduras had sought protection either within their countries or had crossed international borders to escape escalating levels of gang violence and persecution, among other push factors. In this context, children and adolescents are particularly vulnerable. While some young women and girls are victims of sexual violence perpetuated by gang members, young men are exploited for criminal ends, including drug-running, or are fully recruited into criminal groups. Defying the gangs is extremely dangerous, particularly as retaliation not only affects the youth who refuse to join them, but also their family members who become targets of attacks. This persecution significantly hampers families’ ability to find or keep employment, and to access education, health and other social services.

This targeted violence and a lack of overall safety within their communities and countries has driven many families to leave their homes. Nineteen percent of interviewees traveling in families expressly identified violence as the main reason of their displacement. Particularly families from Honduras and El Salvador spoke of death threats, extortions and recruitment by gangs as their principal motivations for the family’s decision to flee their country of origin together. Similarly, 16.5 percent mentioned that violence and threats targeted at them in their country of origin affected their entire family.

“Gang members charged a quota of Q5,000 (USD650) and we paid the first time, but I could not continue paying. They abducted my six-year-old daughter and asked for ransom. They told me that in exchange for releasing her I had to sell drugs. I could not leave my kids at the mercy of the gang members. I had to flee with them. I did not consider any other option. I just wanted to leave Guatemala. I didn’t think about it twice. I headed out without knowing where I would go. I just let the wind guide my journey. My sister tried to convince me to stay, but I had to leave for my children. I am worried about my mother because she did not want to come with us.”

Observing the complexity of the stories gathered during direct conversations with families, the percentage of families being displaced due to the underlying context of violence could be significantly higher. From 2013 through 2018, many parents sent their children and adolescents to other countries to protect them from risks associated with recruitment. As violence in communities has shifted to target entire families, however, hopes for a future in their home countries diminished, and more families began fleeing together.

A high percentage of interviewed families expressed difficulties in securing employment in their places of origin (68 percent), as well as a high percent of children who were not attending school. Only 54 percent of children surveyed were in school, and 4 percent contributed economically to the household. These data highlight the multi-causal and interlinked causes of flight.

The study results underline that adults have few labor opportunities in countries of origin as well as following internal displacement, when they are forced to leave their jobs. At the same time, due to internal displacement children cannot attend school, and families experience reduced access to essential services, increasing their vulnerability and harming their chances of ever rebuilding their lives. When internal movement is no longer a viable option, many people have no other choice but to flee their country.

Of the 636 interviews conducted in the countries of origin (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras) with families at risk of displacement. Forty-four percent of these families reported not feeling safe in their places of residence and living under threats of violence during the six months prior to the study, a reality aggravated for them at night in their communities. Fifteen percent of the families interviewed in this study mentioned facing high levels of insecurity during daytime and this figure doubled when they returned home at the end of the day. A full 43 percent of the families modified the frequency and dynamics of their activities to avoid insecurity.

During the same period, nearly 11 percent of the families had been extorted, and a similar figure had been victims of violence or threats by gangs, while twenty-six percent of families mentioned that their communities are frequently targets of extortion, and 23 percent indicated they had suffered violence and intimidation by gangs.

“In Honduras, the issue with threats and extortion is that it’s not only one person, but perpetrators are either the Mara 18 or MS-13. It’s one person collecting the fee one day, and the next it is another. There are gang members that take over some houses; when someone has their house very well maintained, they come as if they were charging for a commercial service, request an extortion fee and if the family cannot pay they force them out of their home with death threats. When the family leaves, they occupy the house as if they owned it.”

In the event that families leave the country, 22 percent stressed they would flee with the entire family because threats and insecurity put whole families at risk. This information explains the trends seen since 2019 for increasing numbers of family units to flee together rather than as individuals, trends which are in turn a reflection of continued insecurity in northern Central America.

Despite the many risks along the routes, families flee urgently and out of desperation, and often undertake journeys without much preparation. Thirty two percent of the interviewees said they would hire a guide (‘coyote’) and 13 percent would join a large group. There seems to be, however, a lack accessible information on asylum procedures or migratory regulations. Over half of the families (55 percent) were unfamiliar with the requirements to move to another country. Only 28 percent mentioned they would need a passport and 18 percent mentioned identity documents. Whilts 67 percent knew about refugee status, and 63 percent would like to seek asylum, a large number are unfamiliar with the process to do so (71 percent).

On the other hand, having family members in the countries of destination can be an added pull factor for those living in a context of violence; as they often consider family reunification as a way to reach safety. Fifty eight percent of interviewed families in the countries of origin have close relatives abroad. More than a third of these families (39 percent) has considered attempting to reunite with them abroad.

Young Salvadoran works to protect his community from gang violence

©UNHCR/Diana Diaz

Adults often look back at their early teenage years, as some of the best ones of their life – a time when they were young, careless and free; a time when they could make mistakes and learn for the future. But for young men like José*, being careless, free or making mistakes is not an option.

“Being young in El Salvador can be dangerous,” he explains. “When you go out, gangs harass you. They want you to do favours for them, to collect their fees for them or alert them when the police are coming.”

Young women are often forced into romantic and sexual relationships with gang members, he adds, and young men are preyed upon to traffic drugs, run errands or become full-time members of the groups.

“It is a difficult decision. If you say no, they threaten you or hurt your family.”

Jose is now trying to make his community safer, so others can stay.

“I’ve decided this situation must stop,” he says.

“Violence must not dictate our future. We must regain control of our lives, despite the dangers we face.”

UNHCR is working with the government, as well as humanitarian and development organizations, to spur initiatives that make life safer for displaced people in El Salvador.

“I am part of a group of young people who have been able to open small businesses and attend courses to make them thrive,” Jose says. “This has helped me regain hope.”

Though sometimes paralyzed by fear, he is determined to look forward.

“We cannot lose hope. We can make our dreams come true.”

*Name changed for protection concerns.

Those that had to flee

Forty-one percent of families interviewed outside of their countries of origin were from Honduras, 32 percent from Guatemala and 28 percent from El Salvador. Of these, 66 percent of surveyed persons were mothers or fathers, among whom mothers predominated (63 percent) and averaged 30 years of age.

Most people fled with their immediate nuclear family. Of the persons interviewed transiting through or requesting international protection in Mexico, 31 percent fled with their mother or father. Twenty-six percent fled with their children and a similar percentage fled with a sibling or spouse/partner (18 and 15 percent respectively). A small number (less than five percent) fled with nephews, cousins, aunts or uncles, grandparents or grandchildren. Also, 9 percent confirmed no family member was left behind in the country of origin.

In this sense, many families seem to be opting to flee together from the north of Central America. This is seen, on some occasions, as the only option to avoid personal harm of any of the members of the family in the country of origin.

During qualitative discussions, persons in the context of human mobility highlighted that the process of displacement was complex and resulted from simultaneous factors, but violence was a common theme. For example, in some cases, prior to the cross-border displacement, families fled several times within their country to escape extortions and threats by gangs, and this led to serious economic hardship. Persecution and threats often followed them to new communities. This is a key factor of forced displacement from northern Central America: the causes often combine issues of persecution, security, corruption and the impossibility to make ends meet as a family unit. For this reason, families often reported a lack of employment and a lack of social protection as reasons to leave the country, in addition to other push factors, including violence.

When looking at the survey results taken Mexico, amongst those seeking asylum, nearly half of the families interviewed there (49 percent) identified violence as their main motivation to flee from northern Central America, including death threats (30 percent), extortion (10 percent), recruitment by gangs (6 percent), abuse, domestic violence and sexual violence -including sexual harassment- (3.4 percent), and attempted murder and abduction or kidnapping (0.4 percent). Many of these families who had fled the north of Central America reported undertaking actions to counteract the situations of violence prior to fleeing to Mexico, including to move away from the people threatening or hurting them (30 percent) or filing a criminal report (25 percent).

Extortion, threats and violent attacks force taxi driver to flee

©UNHCR/Diana Diaz

Julio*, 47, husband and father of two, was a taxi driver in Tegucigalpa’s busy streets. “Because of the income we make and the fact that we have to move across the city, taxi drivers are often extorted by gangs,” he says. He was approached daily by gang members to pay their fees.

“But one day I was called to testify, and after that my life turned upside down.”

Julio was called as a witness against a network that was extorting taxi drivers across Honduras, led by the Mara Barrio 18, one of northern Central America’s deadly criminal gangs.

His testimony led to the capture of at least three important members of the gang. However, even though he was made part of the witness protection program, no specific measure was put in place to protect him and his family. “We started receiving a lot of threats, and increased fees by the gang if we wanted to be protected,” He says.

After refusing to pay, and averting several incidents, he was violently attacked. “I was driving in my taxi one day, when I was shot several times.” Julio was hospitalized for several weeks, and upon discharge he moved to another city to preserve his and his family’s lives.

There, he resumed his job as a taxi driver, but began being extorted by two other gangs. “This was the sole source of our income, and these two other extortions were too much. So, I reported it,” says Julio.

What followed were a series of threats and sustained attacks, and a generalized sense of persecution. “I was being followed by a motorcycle everywhere. I was terrified.”

*Name changed for protection concerns.

Gang violence keeps family in El Salvador on edge

©*Marlene

SAN SALVADOR, EL SALVADOR – Marlene* and her 17-year-old son José live in a community surrounded by trees and coffee plantations in western El Salvador.

Marlene considers herself a hard-working and generally cheerful woman. “I give good advice. When I work, I dedicate myself to it,” she said. For the time being, she does not have a job, but this is not her main worry. Gangs in her community are a constant threat to her teenage son’s safety. “We are scared for our sons when they grow up in this community.” An official report revealed that families with young family members are the most affected by internal forced displacement in El Salvador.

“Rival gangs attack the first person they see. That’s how they murdered my son’s uncle. They simply found him on the street, and shot him, his wife and another young man. This is what happens some of the time. They can come any time,” explains Marlene with fear.

The situation in Marlene’s community is just an example of many others in El Salvador. Through protection monitoring efforts, UNHCR has been able to verify that even during the COVID-19 pandemic, violence, robbery and clashes among gangs continue unabated. Thousands of families are forced to flee to save their lives. According to official figures, around 71,500 people have been internally displaced between 2006 and 2016 as a result of violence in El Salvador. This year, at least 86 internally displaced persons in the country and around 75 persons at risk of displacement have approached UNHCR to request counselling and assistance.

Marlene lives alone with her son. Her mother, whom she visits every other week, lives in the Salvadoran capital.

In El Salvador, gangs threaten, extort and recruit without restraint. “My son’s father used to get all the calls. They asked for money. They told us that if we did not pay, they knew our son and would harm him,” Marlene remembers. Official figures in El Salvador show that 24 percent of those forced to flee violence were victims of extortion. Thousands more are at risk of displacement like Marlene and her family. “I live in fear,” she says with clear worry in her voice, adding that José has become her rock. “My son is strong and is very mature,” she adds.

But Marlene fears something bad may happen at any moment. Only in the past month, Marlene recalls how two young men were murdered in her community. “I am always terrified for my son.”

*Name changed for protection concerns.

The official data referred to on this story is available in Profiling study on internal mobility due to violence in El Salvador, Final report, march 2018

Children and adolescents

The study included 359 interviews with children. The average age among those interviewed was 16 years old. Among them, of the total children in transit (189), 30 percent were unaccompanied. Overall, the majority of unaccompanied children were boys (75 percent). Of the total unaccompanied children, eight were mothers and fathers. Two of the mothers, 15 and 16 years old respectively, fled with other adolescents. Among them was a person with disabilities.

In a world ruled by gangs and other criminal organizations and characterized by extreme violence, young men, women and teenagers in northern Central America are particularly vulnerable. Violence, especially death threats associated with recruitment, directly affect children and adolescents. Children described facing several push factors, including different types of violence and the lack of opportunities and services in their countries. Of these children travelling alone, 30 percent identified some type of violence as their main reason of displacement, which in turn affected their ability to access basic rights, including going to school.

Across the region, access to education is severely threatened by the influence of gangs within or around schools, looking to recruit children and teenagers and also threating and attacking teachers. This alone is a cause of displacement, both because children are at heightened risk of recruitment, and because their families hope to find unhindered access to education elsewhere.

“My mother told the gang members that I wanted to leave the neighbourhood I was living in. One of them started to approach me, telling me to hang out with them, to threaten me. One day he told me that if I left, they would harm my brother or hurt me. That I shouldn’t even try to leave because they could get in touch with other gang members elsewhere and find me wherever I went.”

In this context, school dropout rates are high, often linked to the forced displacement of the child or the entire family. It is estimated that nearly 900,000 children are out of school in Honduras. In 2018 alone, 49,000 school children dropped out in El Salvador, as did 227,000 in Guatemala.

In addition to already living in significant poverty and facing the imminent risk of recruitment, in contexts where families must pay gang extortion fees, many children and adolescents in northern Central America feel compelled to help sustain their families. This not only increases school drop-out rates, but also accounts for a significant portion of interviewees who cite the search for livelihood options as a cause for their displacement.

In view of the multiple issues children and adolescents face in these countries, they find themselves in a context where fleeing is often the only viable choice to survive. However, fleeing the country unaccompanied by family members, increases risks exponentially for children. Violence forced a larger proportion of unaccompanied children to flee as compared to those fleeing with their families. Amongst unaccompanied children, 21 percent reported fleeing death threats, 5 percent said to be fleeing gang recruitment, 2 percent were running from domestic violence and another 2 percent from extortion.

The cross-border displacement of children, particularly of those fleeing unaccompanied by family members, often turns into repeated attempts to reach Mexico or the United States, fueled by smugglers offering multiple trips. Of unaccompanied children interviewed in transit, 66 percent noted that in the event that they would be detained and deported to their country of origin, they would try to flee their country again and 25 percent of them were already on their second or third attempt to reach the United States or Mexico.

Fifty-four percent of unaccompanied children had considered seeking asylum, compared to 30 percent of the children accompanied by family members. However, neither a majority of unaccompanied nor accompanied children knew where or how to present an asylum claim, highlighting the need to improve the availability of this information. Only 5 percent of unaccompanied children and 8 percent of accompanied children could describe where they could find information on the process for seeking asylum.

The already dangerous journey is even more so for vulnerable groups, such as unaccompanied children. Thirty-two percent of the children that fled with their families stated they had put their physical integrity at risk during the displacement. This indicator increased to 46 percent for unaccompanied children. Eleven children in total mentioned been at risk of sexual exploitation during the displacement, eight of them being unaccompanied children.

Juan, 17, is a Honduran teenager, head of household, that has been forced to flee nine times. He is trying to reach Mexico given the increase in insecurity in his country. Juan mentioned that in the event of being detained and deported to Honduras, he would continue to try to reach Mexico.

Indigenous people

Indigenous families are particularly vulnerable, especially those who were forced to leave their lands and moved to urban areas controlled by criminal groups. Very often, indigenous people flee internally in the hope of one day returning to their land or staying close to family members.

Of the total number of families participating in the study, 12 percent belonged to different indigenous people, and most of these were from Honduras and Guatemala, especially from the border between Guatemala and Mexico. Garifuna families from Guatemala and Honduras are the most represented among those in transit and asylum. Another indigenous people identified during the study, in lower proportions, was the Q’egchi.

Honduran family starts new life across the country, but terror is never far

©UNHCR/Daniel Dreifuss

Three times, Mariana*,42, stood up to the violent gangs that took over her once-idyllic hometown in Honduras. “The first time, they laughed with scorn,” she said. “The second time, they threatened to kill me … and the third, it almost cost us our lives.”

For generations, Mariana’s family lived in peace in the traditional Garifuna enclave, on the northern Caribbean coast. Mariana recalls hot afternoons when her children would play in the shade of the mango trees and coconut palms that flanked the modest home she inherited from her mother.

That all changed around nine years ago, with the arrival of the gangs. The sound of birdsongs and the rhythms of the waves that once echoed through the house were replaced by screams and the sudden crack of gunshots – the sounds of gang members executing those who opposed their reign.

Aaron*, the leader of the gang who had taken over Mariana’s town, took an interest not only in Mariana’s family home – located in the perfect spot for drug trade – but also in one of her daughters, 16-year-old Natalia.* When his notes promising luxury gifts failed to sway the high-schooler, Aaron tried to kidnap Natalia instead.

Aaron and his fellow gang members went after Mariana’s youngest child, Adrián,* then 14, beating him up every time they crossed paths with him. Once again, Mariana confronted Aaron, but once again her bravery backfired. Adrián was shot in the leg.

Mariana realized she had no choice but to flee. She bundled Adrián into a taxi and the two drove about as far away as they could get without crossing any international borders.

As soon as she and Adrián left, the gang took over their house, transforming the family home into a so-called “casa loca,” or “crazy house” in Spanish, where victims are taken to be tortured and killed.

Mariana and her children are among the 247,000 Hondurans estimated to have been internally displaced within the country since 2004 – the vast majority of them fleeing extortion, coercion and targeted threats by gangs and other criminal organizations.

*Name changed for protection concerns.

The dangers of the journey

The average size group of those interviewed undertaking the journey was six people, including many families composed of two. Half of the women and men had children, however the percentage of mothers traveling with children alone is higher (39 percent) than fathers traveling alone with children (19 percent). The majority of families had been on the move for around one month on average, counting from the day they left their country. This timeframe was longer for women as compared to men, highlighting that the journey is much longer, and more dangerous for women, who see the need to take more precautionary measures, such as avoiding traveling during nighttime, and the need to find safe shelter to sleep.

Six percent of the families traveling had a pregnant woman in their group, a similar percentage of families were moving with a person with disabilities, and another five percent included a person with a chronic illness. In addition, families required medicine, medical services and legal counseling, and many mentioned specifically that they had not been able to receive this assistance during their travel.

Needs of families during the Journeys

Forty percent of families reported being in need of shelter during their journey; another 40 percent reported needing food; and 9 percent was in need of clothing. Families faced a range of challenges during their journey: 39 percent reported not having the economic resources to purchase basic goods, including life-saving medicines. Nearly a third mentioned a fear of being detained or of being asked for bribes by authorities for not having legal documentation. In relation to the lack of economic resources, over half of the families (54 percent) cited that they did seek employment during their journey to address their basic needs, although most did not manage to find such employment. Of those that did gain employment, 11 percent were threatened with being reported to authorities by employers.

Conditions of displacement led to unexpected risks along the route. In this regard, 54 percent of the interviewed families mentioned risks such as dangerous means of transportation, extreme weather conditions, sexual violence, robbery, among others. Due to a lack of knowledge of the requirements to cross borders and their irregular migration status, they were forced to take more dangerous routes and didn’t seek help for fear of being detained. Risk factors increased when the family had some people with specific needs –including pregnant women, people with disabilities or with chronic illnesses.

TOP THREE NEEDS OF FAMILIES DURING THEIR JOURNEYS

As noted above, there is a generalized lack of knowledge about the requirements to seek asylum and on processes to migrate regularly. The majority of families do not have information on how to request a visa or asylum, and a quarter was on the move without any documentation. This lack of identity documents during displacement heightens the risk of immigration detention or exacerbates factors of abuse and violence when attempting to avoid it. Additionally, this compelled families on the run to refrain from seeking help when they needed it as they feared they would be found to not have a regular migration status or documentation.

Some people interviewed, including asylum seekers and returned adolescents, when describing the conditions of migratory detention in Mexico pointed out that they were subjected to physical force, intimidation with firearms, food deprivation and that they had to sleep on dirty mattresses smelling of urine. They also indicated that while in detention they were not provided with adequate information about international protection options or on return and deportation procedures.

The most prevalent fear of families in transit who were interviewed was a risk of harm. Nearly half of the families believed their physical integrity was at risk during their journey, and 54 percent of them mentioned the risks were associated with moving through dangerous places. This was followed by the risk of becoming separated from their children, identified by 49 families in transit. Some members of 16 families (of a total of 637) felt at risk of having to resort to survival sex.

Traveling in ‘Caravans’

Between 2018 and early 2020, people from northern Central America formed “caravans” in the hopes of reaching Mexico and the United States. These groups were comprised of persons with international protection needs, as well as those seeking to improve their economic situation or hoping to reunite with family members abroad. A notable feature of these movements were the large numbers of families with children, many citing conditions that made remaining in their countries of origin intolerable.

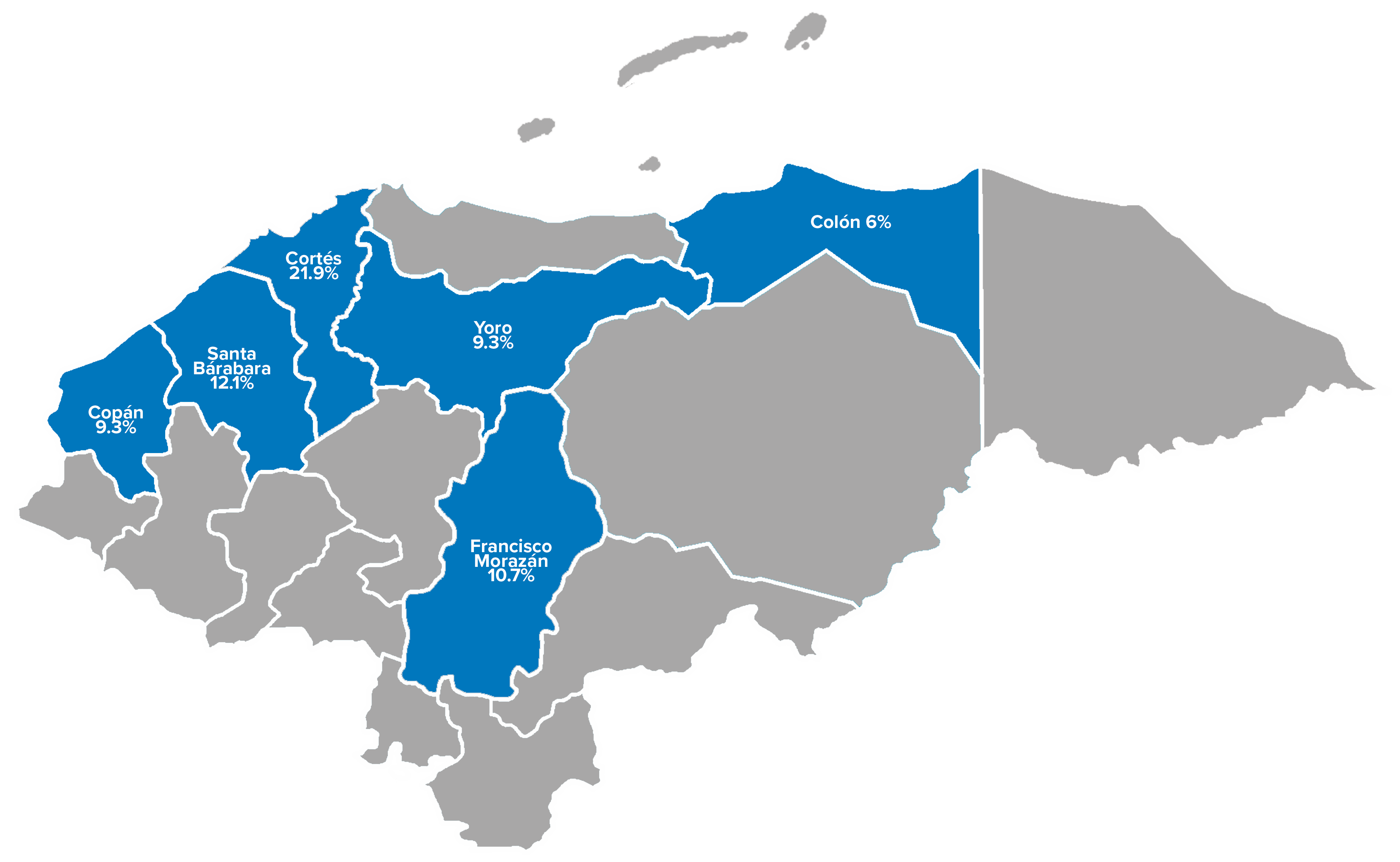

This study included 219 families amongst the “caravan” that departed from Honduras in January 2020. While 70 percent said they were in search of better economic opportunities, nearly 60 percent of them fled from areas that have recorded the highest rates of violence in Honduras. This would indicate the significant impact of violence on the socioeconomic situation of families on the run, pushing them to flee in desperate conditions.

As seen in those fleeing individually, a significant number of families traveling as a part of caravans had planned to seek asylum either in Mexico or the United States (69 percent), but were unfamiliar with the documentation they needed (83.7 percent), how to file an asylum claim (81.9 percent) or the institutions they could ask for help in this regard (88 percent). This reinforces the overall need to invest in public information initiatives about the right to seek asylum for people fleeing violence.

PLACES OF ORIGIN (HONDURAS) OF PEOPLE WHO TRAVELLED IN THE CARAVAN IN JANUARY 2020

“We had to flee our country, thinking about our children’s future”

©UNHCR/Alexis Masciarelli

With tired eyes, unshaven, sweating, Ricardo* chases his toddler on the unused train tracks above the Suchiate river. With his wife, they have decided that they will stop here for the night, in a no man’s land, on a bridge linking Guatemala and Mexico.

“We could no longer live in Honduras”, said the 22-year-old. “There is too much crime. We had to flee for our child’ future, for our family.” So, with his wife, son and a few friends, they traveled northwards. When they are unable to get a seat on a bus, or find space in a car or on the back of a motorbike, others like Ricardo and his family walk for hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of kilometers across Central America. That evening in the Guatemalan border town of Tecún Umán, along with many other families like Ricardo’s, all were hoping for a new beginning away from violence.

In his hometown, Ricardo says that criminal groups had become so powerful that they created a permanent feeling of fear among the residents. “They force people to do things that, often, they don’t want to do. They threaten you. They say: if you don’t do what we tell you, your family will pay the price.” One day, the threat turned real and very personal for Ricardo. “They clearly had been observing me. They knew what time I would go to work in the morning and what time I’d be back home. One day, they came to me and said I should move drugs and weapons for them. The gangs use people like me to do that because we are not suspected and are less likely to be stopped than gang members. They said they would kill me or someone from my family if I refused. I quickly knew we had to flee.”

Within a few days, Ricardo and his family reached the Mexican border although the journey was not without peril. “We were robbed when we crossed into El Salvador. They stole the phone we intended to use to communicate with our family. They took our money. But that did not stop us. We were lucky to find space in a van for some of the route here in Guatemala.” For the family, fleeing with a two-year-old child was not easy. “But despite the struggle we continue with this dream. What we really want is for my child to have a good future.”

*Name changed for protection concerns.

Finding safety

This part of the study was focused on Mexico as a country of asylum, where 437 interviews were undertaken with families from El Salvador (28 percent), Honduras (49 percent) and Guatemala (23 percent).

While it used to be a country of transit for people hoping to reach the U.S., Mexico has increasingly become a destination country for people seeking protection from Central America. Asylum applications in Mexico have soared from around 2,100 in 2014 to over 70,000 by the end of 2019. Of the families interviewed in MExico,49 percent cited violence as the main reason for their displacement, while 91 percent of interviewed families had sought asylum. Of these, 71 percent had their cases pending resolution and 24 percent were already recognized as refugees.

The majority of the asylum-seeking or refugee families in Mexico have access to housing. They described among their main needs: food, medical attention, employment and education for their children. In fact, 58 percent of families have had difficulty accessing food during their time in Mexico, with 26 percent receiving support from the Mexican government, and 38 percent obtaining support from NGOs. Around half of the families had access to medical attention.

Fifty-eight percent of the families sought employment in Mexico. Of these, 64 percent successfully secured a job, 90 percent of which were temporary. A third of the heads of households had informal employment, 24 percent worked for hours or days without a formal contract, 20 percent did not have a job contract, and 14 percent were paid based on completed tasks regardless of how many hours these take. Four percent report begging for money.

Despite Mexico’s many positive efforts to welcome and include asylum seekers, many interviewed families considered their living situation to be difficult. Uncertainty over their migration status, backlogs in the asylum system as a result of increasing claims, coupled with other factors like lack of resources or discrimination, have hindered their access to formal employment, health and education. These situations have not changed during the COVID-19 pandemic and have worsened in many cases. Confinement and quarantines have significantly increased challenges for families in countries of asylum, like Mexico, to become self-sufficient and exercise fundamental rights.

Of the asylum-seeking and refugee children in Mexico who were interviewed, 68 percent were not in school. A high number (68 percent) highlighted a lack of resources to cover the costs of education. Moreover, families mentioned the following additional reasons for their children not being in school: children were not of school age (18 percent), displacement has been recent (3 percent), children must work (3 percent), families fear for their children’s safety (2 percent), the education center is far away (1 percent), bullying at schools (0.4 percent), children must take care of family members (0.4 percent), and disability (0.4 percent).

In terms of housing, 79 percent of the families had secured a place to live. Another 20 percent were staying in a shelter.

Gang and domestic violence drive Honduran mother to exile

©UNHCR/Mónica Vázquez Ruiz

|

The day David’s* father was recruited by a gang, his life to an unexpected turn., with violence forcing them out of their native Honduras. As five-year-old David draws a landscape and daydreams of becoming a taxi driver, his mother Ana* remembers how her love story became a nightmare. “I married one of my childhood friends, and we had a normal relationship until he started to work with the gangs,” she said sitting in her new home in Mexico. As time passed, Ana recalls how he started to become aggressive, violently coming at her and her two sons, the youngest being only a baby. “I couldn’t take the violence anymore, let alone against my two boys. I had to flee and escape from my husband.” With the help of her family, Ana managed to find a place to live with her children, and a job. “My kids stayed with their grandmother while I worked. I still remember David’s first day of school,” said Ana smiling brightly, talking about how her then three-year-old was so happy to go to school and meet new friends. But good times quickly came to an end when Ana ran into her husband in the street, and he followed her home. “He repeatedly threatened me and my kids. I knew I wouldn’t be safe anywhere I went in Honduras,” she said still feeling the pain of leaving her mother behind. The destination was uncertain. All she knew was that she had to leave her job, take her child out of school, leave her life to save herself and her children. Ana, carrying her baby in her arm, and David holding her hand, headed to Mexico where she claimed asylum. Although David had not returned to school yet, he does have a lot of friends. “Everyone here is his friend. He’s very outgoing.” Excerpt from interview by UNHCR staff in Mexico *Name changed for protection concerns. |

CONCLUSIONS

Multiple causes for displacement, all too often underpinned by violence and persecution, has led to over 800,000 Central Americans fleeing their homes, beginning in 2013. Year after year, there has been an increase in individuals fleeing. This was marked initially by especially large numbers of unaccompanied children, then joined in around 2018 with dramatic increases in families units fleeing Central America. Families are forced to flee together as violent threats and persecution by criminal groups in communities extend beyond individuals to entire family units. When the COVID-19 pandemic began, borders closed and numbers dropped Between March and September this year, the number of asylum claims in Mexico dramatically decreased, although the number of claims, especially from adult men has begun to increase again and has now reached the same levels as January. The pandemic has not only resulted in a short term slowing down of the movement, it also led to an exacerbation of the root causes, including an increase in domestic violence, new and continued forms of extortion, and an overall hopelessness in improving the conditions for families to stay. During 2021, we can expect to see the continued flight of not only individuals, but of more families from Central America, seeking safety and opportunity in Mexico, and further north.

There are no easy answers to respond to this continued flight, but we do know that any response must include a comprehensive development plan for the region that targets the underlying root causes of displacement: this has to include addressing all forms of violence and a strengthening of the rule of law and protection systems to ensure protection closer to home, as well as tackling social exclusion, economic under-development, inequality, compromised governance, and environmental degradation. To respond to the immediate protection needs of individuals and families who have had no choice but to flee, States need to guarantee their human rights during all stages of displacement. For one particularly vulnerable group, displaced children and adolescents, this guarantee means putting their best interest first and foremost in all responses and decisions that impact them, whether they are traveling alone or with their families. This includes ensuring international standards against migratory detention for children. Finally, states must make more concerted efforts to address smuggling and trafficking in persons that results in the exploitation of people forced to flee their homes. The combination of addressing root causes, ensuring respect for human rights during flight, and making asylum available for those who cannot safely return to Central America can help meet the needs for families on the run in the future.

NOTE ON METHODOLOGY

This study began in 2019 with the establishment of a working group comprised by technical and specialist staff of CiD Gallup, child protection specialists from UNICEF, and experts on forced displacement from UNHCR. This technical group defined the objectives and approach of the study, the methodology and data collection tools, and finally proceeded with the analysis and validation of inputs.

The study was developed using a mixed methodology composed of an initial quantitative component (surveys with families) and a second qualitative component (in-depth interviews with key people and group sessions with selected profiles). The quantitative component was carried out first, in order to identify possible information gaps to be filled with the qualitative phase.

The quantitative component was carried out between the months of December 2019 and March 2020. A significant sample was taken of each profile interviewed (see annex 1) for a total of 3,104 surveys conducted in Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala and Mexico. The content of each survey was focused on the following profiles:

- Families and children and adolescents at risk of displacement in countries of origin: A total of 789 surveys were carried out with families identified from a non-probabilistic sampling1. The surveys were taken in areas with the highest criminality and violence rates in countries of origin (El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala), which were also areas with a prior history of forced displacement identified through previous studies. The survey questions focused on risks faced by families in their places of origin, including those that would compel them to flee, particularly those related to violence and poverty.

- Families and children and adolescents in transit:A total of 836 surveys were carried out with families identified from a non-probabilistic sampling2. The surveys were taken at locations where persons in transit were typically found in Guatemala and Mexico, such as Casas de Migrantes. For the quantitative component, data of unaccompanied children and adolescents was gatheredin Casa Nuestras Raíces in Guatemala City and Quetzaltenango. This segment of the population was surveyed on the risks they faced during transit as well as the causes of displacement from their countries of origin.

- Families and children and adolescents in country of destination:Through non-probabilistic sampling methods, 453 people were surveyed, the majority of whom were recognized as refugees or asylum seekers in Mexico. Several interviews were facilitated by the UNHCR Office in Mexico in areas with this population profile: Casa del Migrante Monseñor -Oluta Veracruz, Scalabrinianas Misión con Migrantes y Refugiados, State DIF, Municipal DIF, among others. The survey questions for this population focused on the asylum procedure and their living conditions in the country.

- Deported families and children and adolescents: Non-probability cluster sampling. Interviews were conducted with 1,026 families that had been detained and deported during the 12 months prior to the survey. Locations included the Guatemalan Air Force base, outside of the Center for the Comprehensive Assistance to Migrants (CAIM for its acronym in Spanish) and outside of the following locations in Honduras: Center for the Assistance of Migrant Children and Families in Belen, and Center for the Assistance to the Returned Migrant (CAMR) and CAMR-OMOA.

Once the quantitative phase was finalized, a preliminary report was extracted to identify information gaps or issues that required further information to address during the qualitative phase.

This second component was carried out through in-depth interviews and 34 group discussions, segregated according to age, gender and specific diversity profiles in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, as follows:

| Subgroups and inclusion criteria for adults | |

| Subgroup | Specific criteria |

| 1. Women/ Mothers |

Profile A: Who have the intention of leaving their country with their children or other family member, either whom have suffered any type of violence (domestic or other), or face economic difficulties. Profile B: Deported in the last year with a family member. Profile C: In transit through Guatemala or Mexico with a family member. Profile D: Asylum seekers currently residing in Mexico. |

| 2. Men / fathers |

| Subgroups and inclusion criteria for adults | |

| Subgroup | Specific criteria |

| 3. Young and adolescent women |

Profile A: Who have the intention of leaving their country and have suffered any type of violence (domestic or other), or face economic difficulties. Profile B: Deported in the last year. Profile C: In transit through Guatemala or Mexico. Profile D: Asylum seekers currently residing in Mexico. |

| 4. Young and adolescent men |

Focus group discussions were held on issues related to the situation in their countries of origin, risks faced during transit, plans for the future, and knowledge on the asylum procedure. Once the data collection process was finalized, the team cleaned and systematized the information, analyzed the data, and extracted main findings, conclusions and key recommendations.